ART OVER THERE. RASHID JOHNSON: MESSAGE TO OUR FOLKS BY MATTHEW MCLEAN

The Moment of Creation, 2011. Paul and Linda Gotskind Collection, Chicago. Image courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

The Moment of Creation, 2011. Paul and Linda Gotskind Collection, Chicago. Image courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“No true account of Black life can be contained in the English language”. James Baldwin’s proclamation haunts and animates ‘The moment of Creation’ (2011), the work which first grabs the gaze when entering ‘Message to our folks’, the Rashid Johnson retrospective at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta (June 08 2013 – September 08 2013), organized by and debuted at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, the artist’s home town. Its elements, as catalogued by the wall text, declare a deliberate variety: “Mirrored tile, black soap, wax, vinyl, CB radio, plant, books, oyster shells, shea butter, books, space rocks, ink jet photograph on glass”. The point of this diversity being neither sheer randomness, nor museology, but something of the unconsciously semi-structured enunciation of a man asked suddenly to describe his immediate surroundings.

Or perhaps like Adam naming the animals in Eden. Like the characters in NoViolet Bulawo’s recent novel of emigration and exile, these objects say “we need new names”. So the ‘Creation’ promised by the work’s title is the creation of a language – “the goal”, says the artist, “is for all of the material to ‘miscegenate’ into a new language with me as its author”. A reconfiguration of existing terms, the integration of symbolic forms into a new patois — the forceful desire for resolution in the piece is palpable: the streaks of ink, the scratched and smashed glass. But these are also traces of frustration. To compare this work to, say, Johnson’s contemporary Michael Queenland’s ‘Untitled (Black Balloon Rock)’ (2005) — smooth stones enclosed by black balloon rubber, conjuring a world of associative tensions from the barest conjunction of elements – let alone, as some critics have, to Joseph Beuys’ magical language of fat and felt, is to emphasise the extent both of Johnson’s effortful grappling (witness the black-stained glass intermingling with the spread of green leaves – note that too in a work like ‘The Pharaoh’s Garden’ (2009), the artist relies on house plants at least in part to draw together more obstinate, inert objects), as well as the gaps or failures in connection (see the radio mike dangles on its’ cord toward the ground). There are elements here, names for things, but no new words for them, no new language to speak. Instead, the objects remain stubbornly polyglot.

The Moment of Creation, 2011. Installation view. Image courtesy of the artist and Rental Gallery, New York, NY

The Moment of Creation, 2011. Installation view. Image courtesy of the artist and Rental Gallery, New York, NY

It’s a poignant failure, because elsewhere here Johnson’s words can be transformational. ‘Stay Black and Die’ (2007) (from the series ‘Things I gotta Do’) threatens at first with its blatancy, its unapologetic racial drama. And yet the apparent didacticism of the wordage is undermined by the teasing shimmer of glitter in bronze spray paint. Indeed the phrase itself glints and flickers, its meaning shifting Gestalt-like between a sincere, socially-conscious delineation of causation (if you stay black, you’ll die) and unrelenting injunction (you must stay black, even if you die). This doubling, see-sawing on meaning (of the exhibition ‘Shelter’ at the SLG, one writer in Frieze noted the title “left the visitor in doubt as to whether they were being issued an order or an offer”) is current in Johnson’s work. But the shifting or deferral is not infinite – either reading leads to a dead-end, to death, to the black felt in which the shiny words nestle.

Stay Black and Die (3), 2006 from the series “Things I need to do”, 2006. Image courtesy of the artist and Postmasters, New York, NY.

Stay Black and Die (3), 2006 from the series “Things I need to do”, 2006. Image courtesy of the artist and Postmasters, New York, NY.

The inescapability of these of two fatal alternatives leads us towards an understanding of a word that recurs in Johnson’s oeuvre like an incantation: ‘Run’ – what Johnson himself calls “the most powerful word in the English language”. It appears here in an all-white spray paint work (2008).

Run, 2008. Collection of Nancy Delman Portnoy, New York. Photo by Martin Parsekian, courtesy of the artist.

Run, 2008. Collection of Nancy Delman Portnoy, New York. Photo by Martin Parsekian, courtesy of the artist.

’Sweet, sweet runner’ (2010), a video work displayed nearby, takes up the term, enacts it. Departing from Melvin van Peebles’ ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssssss Song’ (1971), the video relocates the black male subject from picaresque liminality to the Big Time, jogging on the Upper East Side and along a busy road. The sun-dappled Central Park is a dream of luxe & calme, the footage’s singular narrative of black social mobility (from Blaxploitation to now) is undercut by the persistent elements in the parallel films – though jogging for health rather than running from authority, Johnson’s subject is still “running for his life”. At the end of the film, words resume their centrality – ‘Watch Out’ flashes in orange text on screen.

Still from “Sweet Sweet Runner”, 2010. © Rashid Johnson. Image courtesy of Salon 94, New York, NY.

Still from “Sweet Sweet Runner”, 2010. © Rashid Johnson. Image courtesy of Salon 94, New York, NY.

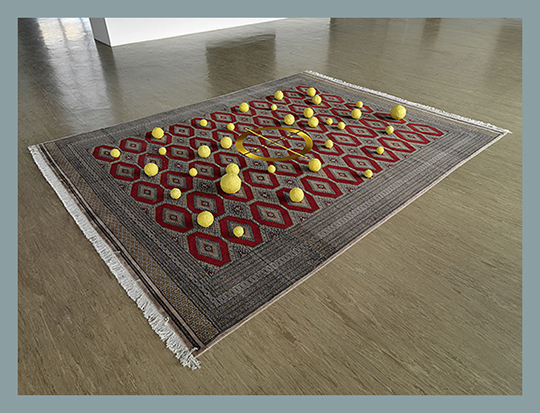

Something of this unending restlessness animates ‘HOW Ya LIke Me NOW’ (2010). For Tom Morton in an essay in Parkett, the work “turns on fluidity, a perpetual refusal to ossify”. On the surface of thing, this is a queer claim, not least because Morton himself identifies the motif of the radical become commodified, luxurious. A Persian rug (standing in for the fetishized ‘Other’?) bears the sniper rifle crosshair motif, adopted from the logo of Public Enemy, and (like the closing slogan of ‘Sweet sweet runner’) an emblem of the constant vigilance central to a certain black experience (one might add, the double experience of being in danger from others and the perception of posing of danger to others), but rendered in an almost-solid surface of gold thread. Balls of Shea butter, a traditionally Afro-Caribbean skin-treatment, painted gold, act as embellished relics of David Hammonds’ ‘BLIZ-aarD BaLL SaLe’ (1983), in which the artist hawked snow balls from a rug outside Cooper Union. Again, a trajectory is being traced here, from an outsider position to one of power, or at least wealth. The richness of material, and the braggadocio of the title attempt celebration. But again Johnson’s words are doubled-edged, and the title reads not as boast but as an invitation to question, deeply insecure. Where are we now, the piece asks. Where have we run to?

How Ya Like Me Now, 2010. Galerie Guido W. Baudach, Berlin. Image courtesy of the artist.

How Ya Like Me Now, 2010. Galerie Guido W. Baudach, Berlin. Image courtesy of the artist.

The exhibition offers elsewhere references to Sun Ra and Afrofuturism, and in this context another aspect of the work emerges – of the golden Shea balls as planets, momentarily frozen in orbit. This sense of hovering or suspension threads together some of the mobile ambiguities that mark the other works discussed — never tied to a single reading, Johnson tries instead to constantly keep all his balls in the air.

Indeed, it is this hovering indeterminacy, rather than Morton’s “instability”, which I believe characterizes Johnson’s most developed work. In ‘…Creation’ the objects fail to materialize the dream of a new, common language precisely in so far as they retain meaningful individuality – just as they have been put together, they can be pulled apart. This refusal to commit leads to works that seem richly open to interpretation, but unrewardingly closed to scrutiny. Like the highly abstract Art Ensemble of Chicago album from which it draws it title, the exhibition is short on “message” – indeed, it can’t even offer a message outside of a self-sabotaging question of identity (“whose folks are your folks, anyway?”).

Yet if the absence of this kind of unity, commitment to a solid, common purpose –of, in other words, a propoganda — is a weakness of the show, it is one of which Johnson provides his own acknowledgement, and partial rejoinder. Alongside the strategies of speaking or running, he offers the initiates of ‘The New Black Yoga’ (2011). Self-absorbed, hermetic, endlessly rotating, these unintelligible, almost farcical gestures offer a combat without violence, a strange kind of beauty. People who appear confidently, like some folks once said of Atlanta, “too busy to hate”.

Still from “The New Black Yoga”, 2011. © 2013 Hauser & Wirth. Image courtesy of the artist.

Still from “The New Black Yoga”, 2011. © 2013 Hauser & Wirth. Image courtesy of the artist.

Matthew McLean is a writer based in London. He has previously written for Modern Painters and Artlyst, and currently studies at the Courtauld Institute.

CLICK ON THE ART OVER THERE LINK ON THE RIGHT FOR MORE